On July 3rd, 1976, Island Records A&R man Richard Williams, who was a frequent contributing Rock journalist to Britain’s foremost music publication Melody Maker, wrote an editorial detailing his recollections of meeting a promising young bunch of musicians and arriving at the decision so sign them under Island’s umbrella of talents, which included the likes of Traffic, John Martyn, Steve Winwood, Free, Cat Stevens but also King Crimson. (Full article below.)

A COUPLE of years back, while I was working at Island Records, that rarest of events occurred: a group of musicians came in with a demo tape which possessed a degree of promise.

Their music was strong and fulsome funk, heavily influenced by the then-current Herbie Hancock album, “Head Hunters,” and it certainly seemed worth the trouble of setting up an audition.

The evening of the audition came round, and on arrival they explained that during the intervening week they’d already changed the bassist and keyboardist.

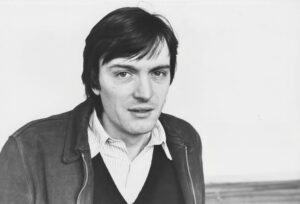

Quite soon I was smiling brightly because they were obviously even better than the tape had suggested, particularly the two guitarists, who swapped lead and rhythm functions like twins. After a couple of minutes, however, I had ears for only one of the musicians: the bassist, a small, wiry, moustachioed individual playing an old brown Gretsch bass with a nonchalance totally belying the powerful noise pumping from his amplifier.

It was his tone that got me first: rich and burbling, with a kind of underwater soft-focus effect while retaining perfect clarity of attack and intonation. Then I began to hear the fills he was playing.

He’d vary the standard metronomic procedure with short figures of astonishing abruptness and complete unpredictability. I couldn’t remotely guess the how or the why of his thought-processes, but every ornamentation sounded absolutely right.

Afterwards I found out that his name was Percy Jones and that his only notable previous employment had been with The Liverpool Scene, and although he was perfectly affable he didn’t seem inclined to vouchsafe any further autobiographical information. On my way home, I began to be convinced that I’d Just heard somebody of great importance.

Across the subsequent months I heard the band a great deal, and became more and more impressed by Percy’s highly individual musical vision. He turned up one day with a fretless Fender instrument, and it turned into a toy under his hands. It might have been invented for him.

Watching the graceful action of his fingers the agility of his runs, and the sureness of his strummed double-stops. I became convinced that he must be converted string-bassist. His reply: “Never touched one.”

One day I went into the rehearsal room, and they said they’d been practicing a tune of Percy’s, the first that I or the rest of the band had heard. It had all the virtues of his playing, notably the constant feeling of surprise and tension and unexpected resolution. It took them some hours to master the piece’s sharp stop-chords, but when they had it right he sounded magnificent. Percy just leaned against his stack, looking for all the world like he’d written a nursery rhyme.

To cut a long (and very complicated) story short, that band became Brand X, so called because they couldn’t decide on a name and we had to have something to put on the studio schedules.

There were changes: the original drummer, and the singer/percussionist, and one of the guitarists all left. Bill Bruford came by for a blow, announced that he wanted to start a band with Percy, and was succeeded by Phil Collins, who stayed on to give the band fresh impetus and inspiration. After months of wrangling they left Island, to my disappointment, and moved to Charisma. Their first album, “Unorthodox Behaviour,” received a suitably laudatory review in this paper recently.

If you hear it, you can’t miss Percy. From the first bar of the first track, his playing simply glows and burns.

For me, he makes more sense than Clarke or Pastorius or Al Johnson or any of the current overpraised Americans. His playing has a weight, and a discretion, and an unshowy kind of imagination that they mostly lack. You can’t help noticing him, but he plays at all times for the common good of the orchestra.

I hope the fact that he’s British doesn’t delay the acclaim he’s due, and I know one thing for sure; his solo album whether it arrives in six months or years, is the one I’m waiting for most avidly.

Richard Williams continues to write in his weekly music newsletter The Blue Moment.